Reboot your immune system with intermittent fasting. Help your ‘good’ bacteria to thrive with a plant-based diet. Move over morning coffee: mushroom tea could bolster your anticancer defences. Claims such as these, linking health, diet and immunity, bombard supermarket shoppers and pervade the news.

Beyond the headlines and product labels, the scientific foundations of many such claims are often based on limited evidence. That’s partly because conducting rigorous studies to track what people eat and the impact of diet is a huge challenge. In addition, the relevance to human health of results from studies of animals and cells isn’t clear and has sometimes been exaggerated for commercial gain, feeding scepticism in nutrition science.

In the past five or so years, however, researchers have developed innovative approaches to nutrition immunology that are helping to close this credibility gap. Whereas nutrition scientists have conventionally studied the long-term impacts of loosely defined Mediterranean or Western diets, for example, today they have access to tools that allow them to zoom in on the short-term effects — both helpful and harmful — of narrower food groups and specific dietary components, and to probe the molecular mechanisms underpinning the effects of foods on immunity.

Mediterranean diet linked to immunotherapy response

The field is starting to attract attention and funding. In April, the New England Journal of Medicine launched a series of review articles on nutrition, immunity and disease, and in January, the US Department of Health and Human Services held its first-ever Food is Medicine summit in Washington DC, which explored links between food insecurity, diet and chronic diseases.

Some researchers argue that modern diets, especially those of the Western world, have skewed our immune responses in ways that have undermined immune resilience. More optimistically, others say that diet could also help to treat a range of health problems, such as cancers and chronic immune disorders such as lupus.

It’s early days, but many scientists in the field are hopeful. “We are learning a lot more about how you can modulate your immune system with single components or combinations of food components,” says immunologist Francesco Siracusa at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf in Hamburg, Germany. As a potential therapy, he says, “the blooming of the personalized nutrition field over the last five to six years is very exciting”.

Fibre and fat

Physicians since Hippocrates have been exploring links between diet and health. In 1912, Polish biochemist Casimir Funk proposed that a lack of essential nutrients he called ‘vitamines’ was causing diseases including scurvy and rickets; later studies of vitamins confirmed their roles in immunity.

In the past decade, the greater availability of ‘omics’ techniques, which can catalogue and analyse entire sets of biomolecules such as genes and proteins in cells or tissues, has helped researchers to unpick the mechanisms by which different diets and dietary components affect the immune system, and therefore health.

Many laboratories are interested in harnessing the immune system to treat one of today’s most pressing health concerns: obesity. Steven Van Dyken, an immunologist at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, has been studying an immune response usually triggered in response to allergens and parasites, to see whether it could help to regulate metabolism.

He and others had previously observed how a type of dietary fibre called chitin, which is abundant in mushrooms, crustaceans and edible insects, activates this immune response, known as type 2 immunity. Van Dyken and his team wondered what effect a high-chitin diet might have on metabolism.

So they fed mice such a diet, and observed that their stomachs stretched much more than did those of mice on a normal diet. The stretching activated type 2 immunity, which in turn triggered a chitin-digesting enzyme. But preventing this enzyme from functioning had noticeable upsides: mice that were genetically modified so that they couldn’t produce the enzyme gained less weight, had less body fat and had better insulin sensitivity than did normal mice when both were fed chitin1. Chitin also triggered increases in levels of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), the hormone that Ozempic (semaglutide) and other similar weight-loss drugs mimic, which helps to suppress appetite.

Edible insects such as these on sale in Bangkok contain high levels of a fibre called chitin, which could be used to help treat obesity.Credit: Enzo Tomasiello/SOPA Images/LightRocket/Getty

Tuning the relationship between chitin, immunity and health — by reducing levels of the chitin-digesting enzyme, for example — could inform the development of therapies such as appetite-suppressing drugs. “Previous research has shown that chitin may activate similar human immune responses,” says Van Dyken. Tweaking these immune responses using chitin and the enzyme might “represent a therapeutic target for metabolic diseases such as obesity”, he says. Van Dyken is an inventor on patent applications related to using chitin and the enzyme in therapies for respiratory and metabolic diseases.

The links between obesity, immunity and health don’t end there. Psoriasis, an autoimmune condition in which skin cells accumulate in dry, scaly patches, is two to three times more common in people with obesity than in those without. And weight loss has been shown to improve psoriatic symptoms.

Immunologist Chaoran Li at the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia, wanted to know how obesity disrupts the skin’s immune system. Previous research had shown how high-fat diets drive psoriasis through increased activation of immune cells that cause inflammation. Using RNA sequencing, Li and his team inventoried skin immune cells in lean mice, and found a population of T cells that usually keep psoriasis-causing inflammation in check2. But when they looked for the same cells in obese mice on a high-fat diet, they found much lower levels — along with elevated psoriatic inflammation. By searching data from studies of cells taken from people with psoriasis, Li also found the same cells disrupted as in mice.

Although Li is focused on the basic mechanisms involved, he hopes that his work will help to improve treatments for the condition.

Feast and famine

If overeating and obesity harm health in multiple ways, could forgoing food have the opposite effect? And might the immune system play a key part here, too?

Evidence is building that fasting reduces the risks of a broad sweep of conditions, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, diabetes and asthma, in some cases through the immune system. For example, fasting has been shown to reduce the number of circulating monocytes, cells that defend the body against foreign invaders but that can be a hallmark of several autoimmune conditions3.

Some researchers think that they can use such evidence to treat people with these conditions without them needing to eat less. For instance, Cheng Zhan, a neuroscientist at the University of Science and Technology of China in Hefei, wanted to investigate a group of neurons in the brainstem that helps to regulate the immune system, to see whether manipulating them could elicit the desired effect.

Yo-yo dieting accelerates cardiovascular disease by reprogramming the immune system

In a paper published in January, Zhan and his team demonstrated that these neurons were activated in mice in response to fasting, and that they caused T cells to retreat from the blood, spleen and lymph nodes to their central reservoir, the bone marrow4. Zhan also used a mouse model of the autoimmune disease multiple sclerosis to show that the continuous activation of these neurons significantly alleviated paralysis, prevented disease-related weight loss and increased survival.

Zhan says that findings such as these could enable people to reap the benefits of fasting — without actually going hungry. “These neurons can be activated with electrical stimulation, small molecules or other activities,” he says.

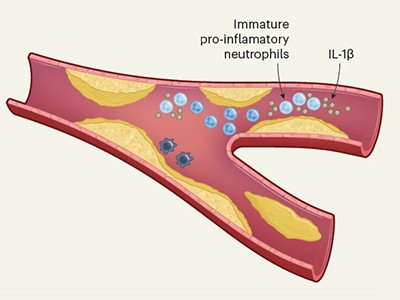

Although evidence supporting fasting as a therapy has grown in the past decade or so, cutting back on calories could have detrimental effects in some circumstances. For example, it could blunt immune responses. In a study published last year, Filip Swirski, an immunologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, and his colleagues recorded a 90% reduction in monocytes circulating in the blood of fasting mice, and an increase in these cells in the bone marrow, where they are produced5.

When the mice were fed after fasting for 24 hours, the monocytes flooded back into the blood in unusually large numbers, causing monocytosis, a condition usually associated with infectious and autoimmune disease. These post-fasting monocytes also lived longer than normal and had a lower-than-usual threshold for triggering inflammation. When the researchers infected the mice that had fasted with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a common cause of bacterial pneumonia, the animals died sooner and in larger numbers than did non-fasted controls.

Common sweetener suppresses mouse immune system — in high doses

Swirski thinks that the body preserves its stock of monocytes as a protective mechanism while energy reserves are low. However, if fasting is prolonged, the costs can outweigh the benefits.

Further work is needed to understand the implications of the study in humans, but Swirski says it might warn against excessive or lengthy fasting. “There is plenty of evidence that fasting can be beneficial, but sometimes it’s about finding a balance and not pushing your system to extremes.” Swirski himself tends to skip lunch, “but I would not want to fast excessively”, he says.

Fasting redistributes immune cells within hours. And other changes in diet can prompt similarly rapid, short-lived changes to immunity. Studying those changes is helpful for researchers, in part because it helps them to avoid the confounding factors that can undermine research into long-term dietary changes, says Siracusa. He has studied the impact of ‘feast diets’ — the tendency to overindulge in energy-dense, high-fat foods.

Siracusa and colleagues fed mice an ‘indulgent’ low-fibre, high-fat diet for three days, then a normal diet for three days, before repeating the cycle. The switch to the high-fat diet suppressed immunity and made mice more susceptible to bacterial infection6. It reduced the number and undermined the function of certain T cells that help the body to detect and memorize pathogens; further tests showed that the lack of fibre impaired the gut microbiome, which usually supports these T cells. “I was surprised that changing the diet for just three days was enough time to see these dramatic effects on adaptive immune-system cells,” adds Siracusa.

When Siracusa asked six human volunteers to switch from a high-fibre to low-fibre diet, he saw similar effects on their T cells. The effects — as with any holiday feast — were transient, but Siracusa thinks that looking at these early immune events relating to changes in diet could reveal insights into the causes of chronic immune conditions. However, he emphasizes that he would not make dietary recommendations on the basis of this small proof-of-principle experiment. Furthermore, work in mice can provide only clues as to what happens in humans.

Human trials

Confirming those clues in people can be difficult. Precisely controlling what study participants eat over long periods is challenging, as is getting them to accurately recall and record their diets each day. “One approach is to ask people to just eat the food you provide for them,” says integrative physiologist Kevin Hall at the US National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases in Bethesda, Maryland. “However, we know that when you do so, they consume 400 calories of off-study food on average.”

So Hall and his colleagues have taken things a step further. Over the past decade, they have done a number of trials in which volunteers agreed to be confined to a ward at a US National Institutes of Health research hospital, in which their diets could be strictly controlled and their responses measured.

Although Hall’s main interests revolve around the effects of different diets on metabolism and body composition — his group has studied the effects of ultraprocessed foods on weight gain, for example — for a 2024 study, he worked with immunologist Yasmine Belkaid, then at the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, in Bethesda, to investigate immune-system changes prompted by different diets.

A participant in a four-week diet study wakes up at a US National Institutes of Health facility.Credit: Christine Kao

Hall and Belkaid, who is now president of the Pasteur Institute in Paris, enlisted 20 adults for a four-week hospital stay and randomized them to follow either a ketogenic diet (one based on animal products and with low levels of carbohydrate) or a vegan, low-fat diet for the first two weeks, then the alternate diet for the final two weeks. Blood samples showed that shifting to either diet was linked to clear changes in both the numbers of different immune cells and which genes were being activated in them7.

While on the ketogenic diet, participants had enhanced levels and activity of T and B cells that form part of the adaptive immune system, which mounts a ‘precision’ response that recognizes specific foes. Those on the vegan diet saw enhanced innate immune responses, which are quicker and less specific than adaptive responses. Belkaid was delighted to see such clear results and is excited at their clinical potential, but refuses to offer dietary advice on the basis of them at this stage. Yet, despite differences in age, genetics and body weight, she says, “it was surprising to see how convergent the immune-system effects were” in just two weeks. “The next step is to test dietary interventions for specific conditions in clinical trials that are as rigorous as those we do for drugs,” she says.

Hall’s group is considering including people with lupus in a study, to compare the effects of different diets. Others have done preliminary studies on the use of ketogenic diets as add-on therapies for psoriasis8 and type 1 diabetes9. There has also been a substantial increase in research into the use of diet and nutrition to boost the effects of therapies that co-opt the immune system to target cancer10. One study, published in 2021, found that higher dietary-fibre consumption was associated with improved survival in people receiving an immunotherapy for melanoma, and that mice with melanomas and that were fed a low-fibre diet had fewer killer T cells — which attack cancer cells — near their tumours11.

Belkaid acknowledges there is still much more work to do to unpick the effects of specific diets on the immune systems of those with different health conditions. However, she and Siracusa are among a growing group of immunologists who are optimistic that the mechanistic insights they and others are uncovering are the first steps towards personalized diets for a range of medical conditions. “I can imagine a world, in the next 10 years, in which we have access to rigorous dietary advice that can be applied in a range of clinical settings,” she says. “I think highly informed nutrition has enormous clinical potential.”