The first time I witnessed death’s aftermath at work, my world tilted on its axis. It was 2002, and a terrorist attack targeted a Christian hospital in Taxila, a city near the Pakistani capital Islamabad. As I walked through the scene, my head grew heavy and my heart thumped. The smell of blood and explosives seemed to press down on me, making each step feel like wading through water. As a young journalist then, barely seasoned in the field, I was unprepared for how the reality of destruction would differ from the detached reports I’d read in newspapers or seen on television.

Each story of destruction carries its own unique signature, but journalists learn to recognise the familiar patterns: the initial chaos, the desperate search for survivors, the gradual transition from rescue to recovery, the sombre task of counting the dead. My first encounter with this world of devastation taught me how inadequate such patterns are in capturing the raw reality of human suffering. The scene from 2002 remains seared in my memory – like the deep red stain that seeped into the cracks of the stone tiles in the hospital chapel, as we reporters and emergency workers stepped cautiously around it.

Amid the wreckage of that day, my colleagues and I interviewed survivors and witnesses. One woman recounted how she had been praying when the explosion shattered the silence, sending shards of glass and wooden pews flying. A rescue worker, his hands trembling, described carrying an injured nurse to safety, her white uniform blood-soaked. The weight of their words pressed down on me heavily. Driving back to Islamabad, I found myself choking for some moments, my body’s visceral response to the horror I’d witnessed. That night, and for many nights after, the images of destruction haunted me. But I also realised then that, if I was to continue in this profession, something would have to change. I couldn’t survive being this raw, this exposed to the trauma I was documenting.

Being an unwilling cartographer of tragedy is not easy. Over the years since 2002, I have stood in the aftermath of suicide bombings and terror attacks in cities across Pakistan – Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Lahore, Karachi, Quetta – where streets were littered with remnants of interrupted lives: shattered storefronts, bloodstained walls, scattered shoes. In the ruins of earthquakes, I’ve tailed rescue workers clawing through rubble in a desperate race against time. I’ve reported on train derailments, bus accidents and plane crashes where twisted metal and scorched earth told stories of journeys ended too soon.

Some experiences remain particularly vivid. In 2005, I was in Muzaffarabad, the capital of Pakistani-controlled Kashmir, after the devastating earthquake that killed at least 70,000 people. There, I met Irshad Ahmed Buchh, a man I had interviewed months earlier during the hopeful launch of a cross-border bus service meant to reunite families separated by wars between India and Pakistan. At the time, he was elated, believing the service would bring long-awaited happiness to divided families. Months later, I found him sitting outside his ruined home, his wife buried beneath the rubble. The optimism with which he had spoken seemed like a distant, almost futile memory.

A few days later, I saw him in the bazaar, talking to a group of men, gesturing as he spoke. His posture was composed, his face unreadable. I wanted to stop, to ask how he was managing. But I didn’t. I kept driving. In that moment, I realised something had changed in me. I was learning to keep grief at a distance. It was perhaps the first time I recognised in myself the development of professional distance – a protective shell that allowed me to function amid recurring tragedies.

This ability to function amid tragedy was about finding ways to bear witness professionally

In Garhi Habibullah, during the same reporting trip, I visited collapsed school buildings where children were buried beneath the rubble; watched distraught fathers dig through debris while mothers wailed nearby. Hearing one woman’s voice calling out her daughter’s name over and over was a deeply crushing moment. Yet, again, I found myself cataloguing the scene with measured detachment. I saw a grandmother moving from person to person, embracing them and asking why death had visited them. I saw mass graves being dug under the October sun. These scenes became entries in my reporter’s notebook, carefully recorded but held at arm’s length as if I was viewing them through a protective glass screen.

Each assignment in the years following reinforced my professional shell. I developed a systematic approach to documenting tragedy: first establish the facts, then gather eyewitness accounts, then weave together the human stories that might help readers comprehend the true impact of what had occurred. This methodology became my anchor, allowing me to maintain composure in the face of devastation. By 2007, when covering a suicide bombing targeting the then-president Pervez Musharraf that killed seven people, I thought I had mastered this professional removal. I was struck by how quickly even the rescue workers and city officials had tried to tidy away the after-effects of the bombing and restore order. How quickly normality was reimposed. In time, I learnt to interview bereaved family members with genuine empathy while maintaining the professional focus and distance needed to tell their stories accurately. I could document scenes of devastation with the precision and detail they deserved. This ability to function amid tragedy wasn’t about becoming callous – it was about finding ways to bear witness professionally, and ensure these stories were told with the gravity and respect they demanded.

For years, I convinced myself that professional detachment was enough. Then on 1 December 2024, my carefully constructed world shattered. The knock on my door came late evening – our cook, pale-faced, telling me something was wrong with my father. I rushed downstairs to find my father gasping for air, my mother hovering helplessly nearby. In that moment, I was no longer the seasoned journalist who had covered countless deaths. I was just a son, watching his father die.

The drive to the hospital was a nightmare that I had reported dozens of times but never lived through: the chaotic traffic, the ambulance ahead of me, its emergency lights flashing, and my desperate prayers that felt like bargaining with fate. I was now on the inside of a story I had written about so many times before, but this time there was no notebook to hide behind.

Though my father’s health had been concerning in recent months, the possibility of losing him seemed distant, a bridge to cross at some indeterminate point in the future. Now I seemed to be an accessory to the dreaded loss. At the hospital, I struggled to find parking, before rushing to the emergency room. Outside the building, the ambulance driver told me doctors were performing an ECG, and so I walked on, believing medical intervention would help my father recover. But then I saw my mother at the hospital entrance, tears streaming down her face: ‘Salman, your daddy has died.’ Her impossible words felt like knives. He was 78. Pushing past medical staff to reach the resuscitation bay, I found my father motionless and all my years of professional distance dissolved into nothingness. My father’s whole life with our family flashed before my eyes in seconds, then faded to black.

One of the hardest moments following his death came during the ghusl, the Islamic ritual of washing the body before burial. My brother Faisal, my paternal uncle and I performed the ritual on our house’s patio. As I stroked my father’s face and ran my fingers through his hair, I thought of all the bodies I had seen in my career – strangers to me, but beloved to someone – and the professional and personal collapsed. I saw that no amount of reporting on death could have prepared me for the intimacy and pain of losing someone you love.

His absence was not just a void in our home: it was a silence that filled every corner

The ritual became a profound lesson in the physicality of loss. Each gentle movement, each careful touch, was both farewell and reconnection. The water flowing over his skin, the soft cloth we used to dry him – these sensory details had an intensity no amount of professional documentation could ever match. During those moments, it almost felt as though my father might suddenly return. Faisal, who performed the rites stoically, later confessed to having the same feeling: even as he knew that mortality is a door we must all walk through, it seemed as if our father would suddenly wake up.

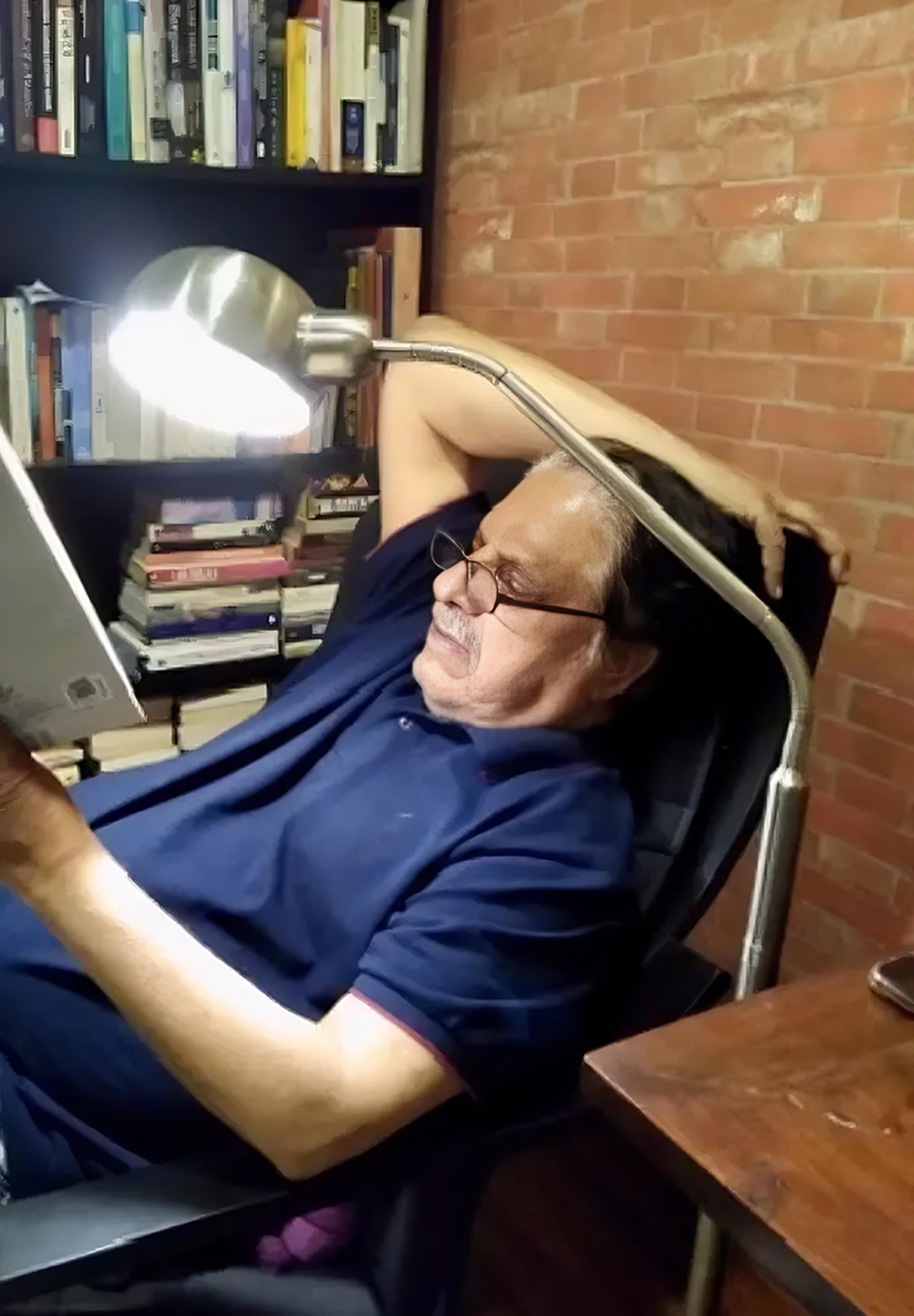

My father, Chaudhry Masood Ahmed, was an economist. He’d studied at Vanderbilt University in Tennessee on a scholarship in 1978-79, then worked for the Pakistani government till his retirement. His study in our Islamabad home was a sanctuary filled with books on philosophy, politics and religion. Even in his later years, he’d ask me to recommend books or essays to ‘explain the current paradigm of the world’. I would tease him, saying he should be explaining it to me. Smiling, he’d say he wanted to know the latest trends.

In the days after his death, I searched for bearings in this new terrain. His absence was not just a void in our home: it was a silence that filled every corner. His study, once alive with his presence, felt empty and desultory. One night, I sat in his chair and found myself burdened by the weight of memory. Everything was there, neatly arranged as he liked it, yet nothing was the same. Death creates distances that feel impossible to cross. When a loved one dies, the chasm that suddenly opens feels almost cosmic in its expanse. Time becomes elastic, stretching moments of sorrow into eternities. The familiar becomes foreign, as though the very fabric of our existence has been torn. We search for escape routes from this new reality, but there are no emergency exits offering quick passage back to what was.

Grief, as the psychotherapist Robert A Neimeyer notes, is not just an emotional void – it is a rupture in our narrative of existence. It carves new fault lines through our understanding of the world, rearranging what we thought was fixed and known. The old landmarks of certainty, routine and control disappear, leaving us to stumble through a landscape defined by absence.

One of my favourite photographs shows my father in his study chair, holding a book, light spilling over him, illuminating the quiet contentment on his face. It is how I like to remember him. He seems irretrievably far and yet ineffably close. It reminds me that while death creates distances that feel impossible to cross, the connections forged by love endure. I have also come to understand that my years of documenting the grief of others were a preparation of a different kind – not for the pain itself, but for an understanding that grief, in all its forms, is a testament to the depth of human connection. As a journalist, who continues to bear witness to loss, I’ve a deeper appreciation for the nature of those moments, and profound gratitude to those who share their stories of grief with me.